Why I’m Voting for Elizabeth Warren

I’m voting for Elizabeth Warren. I’m explaining my thinking in the hope that it might help you think through your decision (even if you decide I’m wrong).

The “We Must Beat Trump” Electability Argument

Like many people, my priority is saving the country from another devastating Trump term.

The Only Way to Beat Trump Is ...

Some friends have passionately urged me to vote for Sanders because he’s the “real deal” in terms of driving change: He’ll fire up both new, young voters and older people who were too discouraged to bother voting in 2016. The only way to beat Trump, they say, is to get those people to vote.

Other friends have urged me to vote for KB3 (Klobuchar, Biden, Bloomberg, or Buttigieg) as the candidate most likely to beat Trump because KB3 can attract crossover Republicans who are disgusted with Trump but won’t vote for a lefty like SW (Sanders or Warren). The only way to beat Trump, they say, is to attract crossover Republicans and independents.

Others have said that a KB3 nominee will make them sit out the election, or maybe even vote for Trump because they want to send a message to the Democratic Party that more corporate-connected, centrist candidates and policies are unacceptable.

And still others say that if SW is the Democratic nominee, they and many others will vote for Trump rather than for a “socialist.”

KB3 it must be if we’re to beat Trump.

I’m Not Convinced

These arguments sound plausible. Pundits and journalists make them. There are no doubt voters in each of these categories. But, how many voters fall into each category? Will SW scare away more centrists and crossover voters than they’ll attract in left-leaning voters? Will KB3 draw in centrists and crossover voters, but lose left-leaning voters who stay home on Election Day?

There’s no convincing evidence that answers these questions. We learned in 2016 that polls aren’t necessarily reliable in this age, not even polls taken close to the election. And talking to friends is even worse because we tend to be friends with people like ourselves.

I conclude this:

Electability is unknowable.

Electability is, therefore, a lousy criterion for choosing a nominee. I’m going to vote for the candidate who I think is best for the country. You should too!

SW or KB3?

The first decision we all have to make is SW or KB3.

We have a ton of problems in the country to solve. We all know them: health care; climate change; the dire economic plight of many at a time of surging overall wealth; the decline of public, affordable, high-quality educational opportunities; the ascendency of lawless, authoritarian oligarchy; infrastructure decline; endless war; racism and white supremacy; attacks on our personal freedoms in the name of religion; a corrupt political system where money dominates and voter suppression is rampant; a tax system that not only doesn’t trickle down but flows up; gun violence; and more.

Both SW and KB3 want to tackle these problems. The difference is in how: KB3 want to make incremental changes within our existing systems; SW want to make big changes — what Warren calls “big structural change” and Sanders calls “political revolution.” This choice in approach is our fundamental choice. So let’s talk about the two approaches to change. We’ll then return later to the SW vs. KB3 decision.

Incremental Change

Benefits

There are important benefits to incremental change.

It is easier to implement than bigger changes. People feel less threatened by it. For example, people who currently have great health care feel much less threatened by the idea of adding a “public option” to Obamacare than the idea of overhauling our medical system with some variant of “Medicare for All”.

Powerful companies also feel less threatened by incremental change because they are confident that they can protect their businesses through using campaign contributions and lobbying to shape the regulations to their favor. (We see this, for example, in the rules that prevent Medicare from negotiating drug prices.)

Another important benefit of incremental change is the ability to experiment: Make a small change, see what happens, learn and adjust, repeat. And, when a mistake is made, the negative impact can be small enough that people are willing to try something else.

The relative stability delivered by incremental change is also important to both people and businesses because it makes long-term planning and decision making possible.

If a company makes a large investment in a factory to build something that we then outlaw or discourage, they have a big problem. And they’ll fight hard against any such change. We’re seeing that now in the energy industry: A power company that invests to build a gas-fired power plant based on a 40-year life expectancy is going to fight hard against renewable energy sources that would prove their investment a mistake.

Likewise, an individual that buys a home that is only affordable because of the tax subsidies provided for homebuyers is going to be very unhappy if we change the rules to remove those subsidies.

Drawbacks

The biggest drawback of incremental change is that it risks “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.”

Ask those people at Kodak who kept improving film and film cameras. Of course, Kodak employees weren’t idiots and they even worked on digital photography technology. But because the company’s management was focused on maintaining their existing business, Kodak couldn’t make the switchover and they now just sputter along a small shadow of themselves. (I’m not picking on Kodak. This behavior is widespread and well understood in the business world, where it is called the “innovator’s dilemma.”)

Look at how incremental change has played out in health care. We all know that our health care system spends spends twice as much as other advanced countries do while delivering inferior results overall and bankrupting many individuals. We’ve been tinkering with how we provide healthcare for almost a century, but the result has been that we continue to have an ever increasingly expensive system that is as much about delivering profit to large insurance and healthcare companies as it is about taking care of people.

We’ve made incremental changes to how we pay for health care. We have introduced employer-provided private insurance (subsidized by hefty tax breaks), Medicare for older and disabled people, Flexible Spending Accounts, high-deductible insurance with Health Savings Accounts, the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, a parallel medical system for veterans, supposedly not-for-profit hospitals that actually generate enormous profits, etc.

Nobody would design such a crazy quilt system. We got to it by a bunch of incremental changes over many years. Is the system going to collapse? Well, no, but it is consuming an increasingly large part of our economy while at the same time hurting many of our citizens. It is hard to imagine how further incremental changes will solve the problems in healthcare.

Again, I don’t mean to pick on health care. It is just one example where incremental change has failed.

Another example is our tax system. People and companies are subject to an enormously convoluted, complex tax system that delivers huge tax breaks to the wealthy and well-connected, but is a substantial burden to most poorer people. The Federal income tax system is so chockablock with tax breaks that a parallel tax system, called the Alternative Minimum Tax, was introduced to make sure that wealthy people pay at least some minimum amount of tax.

Again, nobody would design a tax system like the one we’ve arrived though incremental change over decades.

Big, Structural Change

Whatever you call it, making big changes quickly is disruptive. There will be winners and losers. The people and corporations that believe they will be losers will fight very, very hard to prevent changes or, at very least, blunt the impact of those changes on them.

Generally, support for the changes will be more diffuse than the opposition. Take the health care example. If we try to make big changes, powerful players in the healthcare industry will fight hard against them.

On the other hand, among the many citizens who are happy with their healthcare — call them the happy campers— some will oppose big change and some will recognize that because there are many other citizens with inadequate healthcare, change is necessary. Even among the happy campers who will go along with big changes, few will fight hard for it.

That leaves the people with inadequate healthcare to fight for big change. But they are mostly people without the resources to fight effectively for what would help them.

Bottom line: Building support for big change is very difficult because there will be strong, focused opposition and weaker, diffused support.

Benefits

Nevertheless, big changes can have a huge positive impact. For example: FDR’s New Deal pulled us out of deep recession (helped, to be sure, by World War II industrialization), introduced many worker’s rights, including the work week and minimum wages, provided economic security for many through Social Security and banking reforms, and introduced regulation of the securities industry. More recently, introducing Medicare in the 60’s kept many elderly out of poverty from healthcare costs.

All of these programs encountered fierce opposition at the time they were proposed and passed. And opposition to some continues even to this day. But they have all made a positive difference in the lives of many people.

Drawbacks

Of course, not only is big change hard to achieve, it can go awry. By its very nature, making big changes that affect many people and companies can have unintended side effects. Moreover, the opposition, working legislatively and through the courts, might succeed in changing or dismantling important parts of new programs, further complicating successful implementation.

Never Waste a Good Crisis

Machiavelli evidently first said, “Never waste the opportunity offered by a good crisis.” Winston Churchill popularized Machiavelli by saying “Never let a good crisis go to waste”.

FDR introduced the New Deal in response to the crisis of a deep recession that had people out of work, starving in the streets, and hopeless. People’s savings were wiped out. The crisis made it possible for him to succeed with big change.

Big change usually fails in the face of the strong focused opposition of those threatened by it. But in a crisis situation, the dynamics can change: People who would ordinarily sit on the sidelines become motivated to support change.

That’s where we find ourselves now: There are a lot of angry people.

Tens of millions of people are sufficiently disgruntled about their economic situation to support a populist on the right like Donald Trump, who blames “the politically correct” elite and the other — other races, other nations, the elite, the immigrant, etc. — for the problems of “the people.”

And, there are tens of millions of similarly disgruntled people who support a populist on the left like SW, who blame the wealthy and the “corrupt political establishment” for the problems of “the people.”

History would suggest that something must change, and quickly, or the situation will degenerate into violent revolution, with the outcome uncertain, but with our American democratic “experiment” in real danger.

So, we have maybe not a current crisis, but a series of looming crises. Is this enough to motivate people to accept big change? Or will we have to wait until we have economically-motivated violence, or climate-motivated violence, or racially-motivated violence, or a crisis of nationalism?

SW or KB3 Revisited

No one can predict with certainty whether our looming crises are enough to get people to accept big change. But, it is clear that continuing along our current trajectory is going to lead to an increasingly authoritarian, oligarchic government that will consolidate its power and suppress opposition. Our chance to change the country’s trajectory is to offer a better alternative before it is too late.

For that reason, we must elect SW and not KB3. A government led by KB3 will make incremental improvements, which would be good, but probably not enough to show Trump supporters that there’s a better way than right-wing authoritarian government.

S or W?

So, do we choose S or W? There are two sets of considerations: pragmatic and policy.

Policy

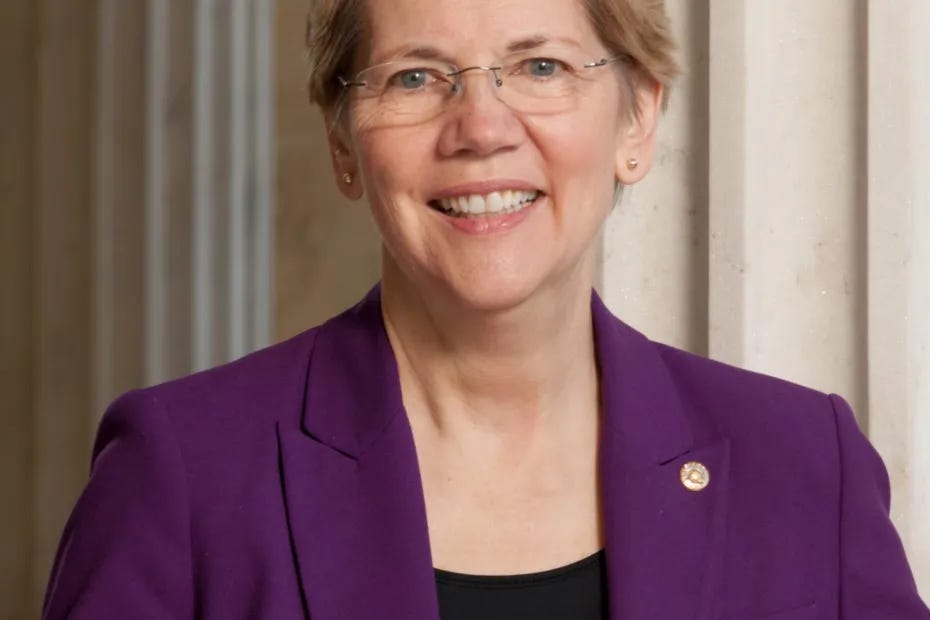

Let me start with the policy questions. Warren has deeply thoughtful policy positions. I don’t agree with all of them. I particularly question whether a wealth tax is practical. But her economic advisers at least have reasonable answers to my concerns in their book.

I have been impressed by Warren’s change on Medicare for All. She heard feedback and she responded. Some on the left are angry about this and she lost a lot of support. That’s misguided: Adapting to feedback while sticking to one’s principles is part of good change management when attempting to do something big.

Warren has worked most of her professional life on policies that affect the economic well-being of people. She has an incredibly deep understanding of how economic policy affects real people. And, with her work to establish the Consumer Financial Protection Board, she has shown that she can translate policy positions into implemented policies.

Sanders, too, has strong policy positions. I don’t find them as compelling and thoughtful as Warren’s, but that doesn’t particularly bother me. What I find disturbing is his dogmatism. He hasn’t shown any flexibility or give and take. Pure idealism might be inspiring, but it is not a practical way to get change accepted.

Pragmatics

Health and Age

Let’s start with the obvious: Sanders will be 79 on Inauguration Day and 87 by the end of his two terms. As much as I’d like to ignore age, people in their 80s often experience significant cognitive decline and lower energy levels. We know from the Reagan experience that those around a President can and will hide such health issues. Sanders has not been as forthcoming post-heart-attack about his medical situation as I’d like. His age and condition is a big risk, although he certainly shows enormous stamina and energy on the campaign trail.

Warren is almost eight years younger than Sanders. Still not an ideal age to become President, but she’d finish her presidency at about the same age as he’d start his, and she doesn’t have any known health issue.

Capitalism

Warren is a full-throated capitalist. She has made this clear. She wants capitalism with guardrails and appropriate regulation. She has shown in her career the ability to craft suitable regulations and create regulatory mechanism. That’s good.

Sanders is a “democratic socialist.” I know what that means and I’m fine with it. But this is a powerful attack vector from Trump and the GOP. I read many of the emails they send to supporters and I can tell you that they hurl “SOCIALISM” at Democrats at every turn. If Sanders is the nominee, this will be a huge problem, which no amount of explaining will solve.

Even without GOP attacks, people recognize that despite the many flaws in our particular version, capitalism has delivered enormous wealth (unevenly) to this country. Any confusion in their minds about “democratic socialism” will be a problem.

Debating Trump

The Democratic nominee will have to debate Trump repeatedly. Sanders has shown a phenomenal ability to deflect and stay on message during the Democratic debates this year and in 2016. It is very powerful. But he hasn’t shown the ability to take on someone like Trump.

Nor has Warren, but her attacks on Bloomberg in the most recent debate show promise that she’d be able to handle Trump. She would certainly rip him to shreds over his lies about the economy. She is without equal debating economic issues.

Anti-Semitism

(As a Jew, writing this paragraph gives me great pain.) Sanders is Jewish. His Judaism might not be an important part of his life, but we can be sure that the Trump campaign will incite anti-Semitic innuendo and code words, just as they incite racial hatred. In a close election, this could matter. A lot.

Leadership & Collegiality

Warren has shown that she can get stuff done at high levels of the Federal government. Her work creating the CFPB was exemplary and she worked both sides of the aisle to do it. How many other lawmakers can boast of creating an effective Federal agency.

Dogmatism

This is pretty squishy, but ... Sanders comes across to me as unyieldingly dogmatic. This may be part of his populist appeal, but I think it will get in the way of actually governing. Warren has strong views, which she states clearly, but she doesn’t have the dogmatism.

Summary

On the surface, KB3 is attractive. After all, can’t we all get along? But, eight years of KB3 would only make incremental progress on our country’s most important problems. KB3 would be dramatically better than another Trump term and if that’s who the Democratic Party nominates, that’s who I’ll support.

But I strongly prefer SW, particularly Warren. I give Sanders tremendous credit for changing the conversation in American politics and for building a coalition of supporters.

Sanders is like Moses reaching the Promised Land. He kept the people together and got them there, but he’s not the right leader to takes us into it. That leader is Warren.