Real Tax Reform: Desiderata

The word desiderata describes perfectly what I want to discuss in this post on real tax reform. I first encountered it taking Professor Fred Brooks’s computer architecture course in grad school in 1977. In his 2010 book, The Design of Design, Brooks defines desiderata as the secondary objectives of a design. Using design of his beach house as an example, the primary goal is to build a beach house. The desiderata are things like being able to survive hurricanes, showcasing the stunning views, and being able to seat and sleep 14 people.

I previously discussed three goals for a tax system, the most important being to raise funds for public services. Let's agree for now not to debate what public services are appropriate nor how much money should be spent to provide those services. Whatever the amount, the money must be raised. That's the goal.

What are the desiderata for a reformed tax system?

Responsive

The country's (or other taxing jurisdiction's) funding needs to change with politics and world events. At times, the country's political leaders will want to lower taxes and reduce services or raise the deficit; at other times they'll want to raise taxes to increase services or lower the deficit. The tax system should be responsive to such changing needs without requiring frequent overhaul of the rules or administrative mechanisms.

Fair

Taxes direct our money to purposes decided by others. History shows that excessive or unfair taxation can foment rebellion. Two questions contribute to perception of fairness or unfairness:

On what are the taxes spent? If most tax revenue goes to support a lavish lifestyle for a large royal family while the serfs starve, rebellion becomes more likely. (Ok, I've been watching Victoria.)

Who is taxed how much? If the serfs are taxed heavily and the aristocracy are not, rebellion becomes more likely.

Logically, these are independent questions, the first answered by a budgeting process and the second answered by the design of the tax system. They're coupled, however, because people are more willing to accept taxation for what they think is a good purpose. They are also coupled when the tax system, as our’s does, treats certain economic activities more or less favorably.

The proposed 2018 Federal government budget calls for spending about four trillion dollars. I don't want to discuss here whether this is too much spending or too little, or whether the money is being spent wisely. That's a question for the budgeting process.

The topic here is tax reform, so let's discuss the second question: Ignoring deficit spending and non-tax revenue sources, how can the the government raise the four trillion dollars in a way that is perceived to be fair?

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports that only 9% of Federal revenue comes from taxes on corporations, so let's follow the money and discuss taxes on individuals.

Individuals in the US are subject to multiple taxes, including income taxes levied by Federal, state, and local authorities, so-called payroll taxes (e.g., Social Security and Medicare), sales taxes, property taxes, gift taxes, and inheritance taxes. Since the direct economic impact on an individual (or family) comes from the sum of all of these taxes, the important question to ask is how much total tax do particular categories of people pay.

The simplest idea of fairness is that everyone should pay a fixed amount. Dividing the $4T Federal budget by the 259 million people over the age of 15 who plausibly might be able to work, shows that each potential worker would need to be taxed over $15,000, about the earnings of a full-time minimum-wage worker. So, taxing everyone a fixed amount isn't feasible. I'm not aware of any serious proposal to structure our taxes this way, but I've heard it mentioned in conversation.

There are serious proposals to structure taxes so that everyone pays a fixed percentage of their earnings (or, alternatively, of their consumption) in taxes. A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that this is feasible: The Census Bureau reports that the 2016 mean per capita income in the US for the 259 million people over age 15 was about about $46,000, giving a total income of just under $12 trillion, excluding investment earnings. So, taxing all workers a third of their earnings would, alone, be sufficient to fund the Federal government.

In practice, investment income and corporations might also be taxed so that the fixed percentage could be lower, perhaps much lower. This kind of taxation is often called a flat rate tax or simply a flat tax. The latter term is confusing and could be mistaken for a fixed amount tax, so I don't use it.

Some countries and about ten US states use flat-rate income taxes. Most states and localities use flat-rate sales taxes.

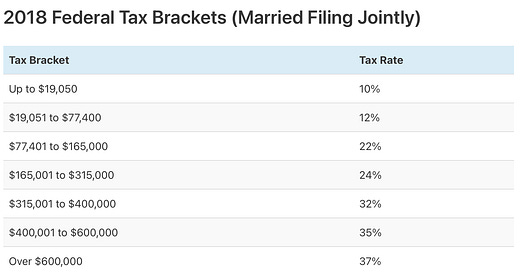

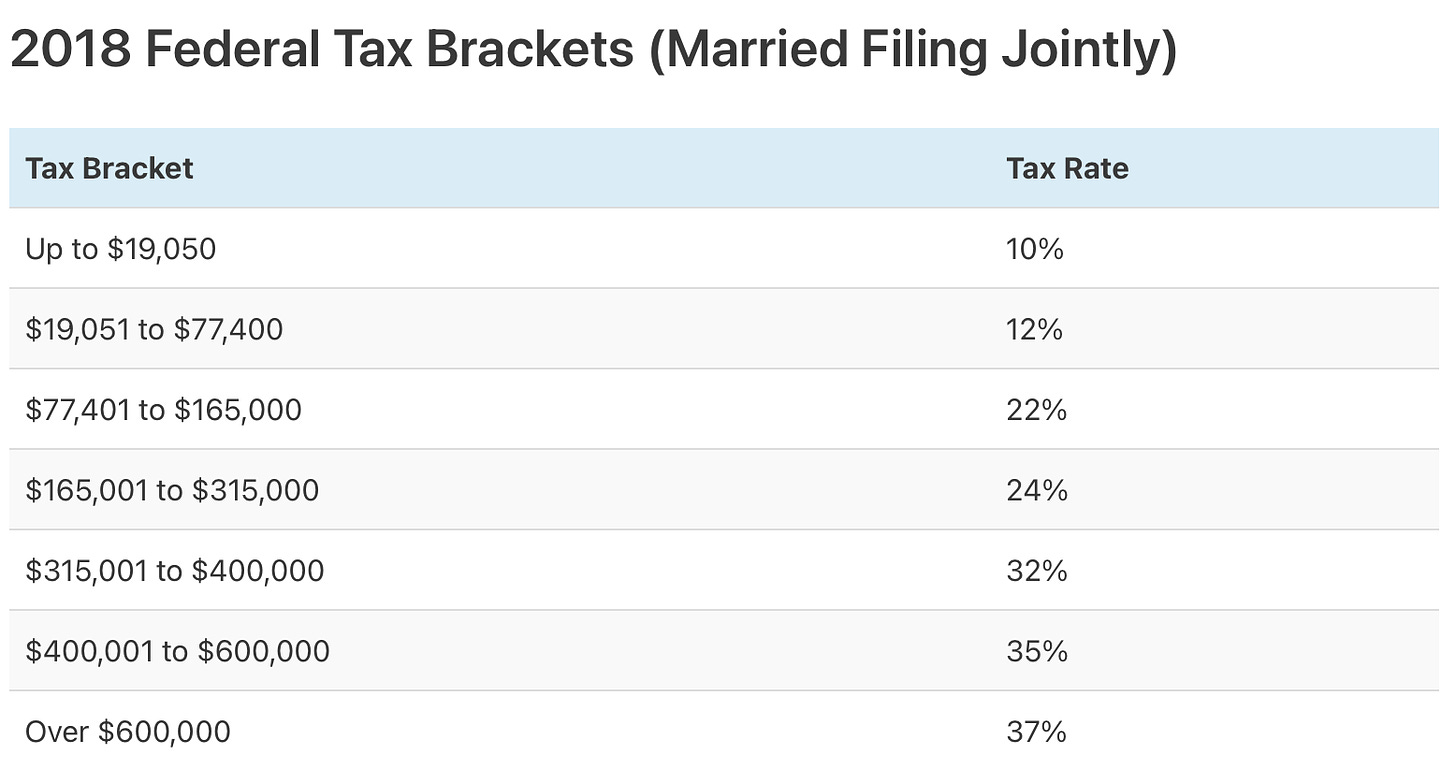

A progressive tax is one in which people with larger earnings pay a higher percentage of their income as taxes than people with smaller earnings. Usually, this is structured as a sequence of tax brackets, where income in certain ranges is taxed at a particular rate, with the rates increasing as income increases. The Federal income tax is structured this way, if one ignores the impact of various deductions and exceptions. The top rate for a particular income is called the marginal rate because this is the rate paid on the next dollar earned.

It is important to understand that the marginal rate is not the percentage of income paid. As an example, here’s the 2018 tax rate table for a married couple filing jointly:

A couple earning $175,000 would get a $24,000 standard deduction, yielding a taxable income of $151,000. The table shows a marginal rate of 22%, but the amount of tax is $25,099, which 14.3% of the total income, not 22%. Politicians who think taxes are too high often talk about the marginal rate in a way that makes people believe that that's what's paid. It is not.

Federal income taxes in the 1950s through 1970s were dramatically more progressive than they are today. During the 1950s, for example, the top marginal rate was over 90%. With the tax law passed in 2018, the top marginal rate is 37%.

A regressive tax is one in which lower-income people pay a higher percentage than higher-income people. Regressive taxes are usually considered unfair because it seems unreasonable for people "who can afford it" to pay less than someone struggling to get by.

One never hears praise for the fairness of regressive taxation, yet regressive taxes are common. The Social Security tax is regressive because everyone pays 6.2% of income up to a limit ($128,400 in 2018), then zero on everything above the limit. So, for example, someone earning $50,000 pays 6.2%, while someone earning $10M, pays just under .08%.

Some taxes appear to be flat-rate, but their impact is regressive. State and local sales taxes are a good example. Everyone pays the same rate of sales tax, but since poorer people must spend most or all of their income, their effective tax rate is close to the stated rate of the sales tax. Wealthy people, however, spend much less than they earn, making their effective sales tax rate much smaller.

Similarly, the marginal tax rate on long-term (one year or more) capital gains is 23.8% (20% on capital gains, plus 3.8% net investment tax on high-income people), much lower than than the 37% marginal rate on ordinary income. Since high-earning people usually earn much of their income from capital gains, and most lower- and middle-income people earn primarily ordinary income, the effect is regressive: the wealthy person pays a lower overall rate than the middle-income person. A famous example is Warren Buffett's statement that he pays the lowest tax rate of everyone in his office, including that of his secretary. Buffett's low rate comes from this preferential taxing of capital gains.

Two arguments are made that progressive taxation is the fairest kind of taxation:

High-income people are able to pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes with much less impact on their lifestyle than people with lower incomes. For example, even if a person earning a billion dollars paid the 37% marginal rate (which would never happen), they would still have $630 million after taxes, an unimaginable amount of money to most people.

People with higher incomes benefit more from public services than people with lower incomes, and therefore ought to pay higher taxes to support those services. For example, people who own companies benefit from the public investment in education, infrastructure, legal system, police protection, research and development, etc.

These arguments are not universally accepted, and many people who lean politically to the right oppose progressive taxation, while many people who lean politically left support progressive taxation. I will devote a separate post to discussing the pros and cons of progressive taxation.

My personal opinion is that taxes in a democracy should be strongly progressive. As a country, we have been moving in the opposite direction since the 1970s.

Simple and Transparent

The Federal tax code is enormously complicated. Understanding and obeying the tax code takes a legion of accountants, tax attorneys, other tax practitioners, and an entire category of software products. Evading taxes, legally, likewise is a whole industry, both for individuals and large corporations. At least people earn a living doing all of the work that derives from the tax code's complexity.

As reported in The NY Times, House Speaker Paul Ryan recognized the need for simplicity when he said of the tax reform effort: “We’re making things so simple — we’re making things so simple that you can do your taxes on a form the size of a postcard.” Unfortunately, there's little simplicity in the 1097 pages of the tax reform bill. Check out, for example, the text on page 141 defining "rules for plants bearing fruits and nuts".

The wasted effort caused by the complexity is one thing. I'm more concerned with how the complexity enables politicians to hide tax breaks from public scrutiny.

Indeed, how many members of Congress read and understood the 1097 pages of the tax bill in the short time between when they received the text and when they voted?

How many citizens understand that Federal revenue lost through tax breaks embedded in the Federal tax code, so-called tax expenditures, are larger than the defense budget, larger than Medicare spending (net of revenues), and larger than Social Security Spending? And how many citizens know that the Congressional Budget Office estimates that "more than half of the combined benefits of 10 major tax expenditures would accrue to households with income in the highest quintile (that is, the highest fifth) of the population; furthermore, 17 percent would go to households in the top 1 percent. In contrast, 13 percent of those tax expenditures would accrue to households in the middle quintile and only 8 percent to those in the lowest quintile."

Politicians structure the tax code to be able to say one thing and do another. With real tax reform, the system would be simple and transparent enough that citizens could understand the tax breaks that the politicians hand out.

Enforceable and Difficult to Evade

Tax law must be enforceable. In other words, if you break the law you should expect to get caught. If not, revenue will be lost and people will think that taxes are unfair.

Equally important, if provisions of the tax code interact to make it possible to recast income in ways that avoid (legally) certain taxes, those provisions will be used to evade taxes. Here is a common example from the days before most upper middle-class people became exempt from inheritance tax: an individual would create a trust for the benefit of his or her children; the trust would buy a life insurance policy on the life of the individual; each year, the individual would gift his or her children the money to pay the annual insurance premium (usually small enough to avoid gift tax); when the individual dies, the trust receives the insurance benefit, which flows to the children free of inheritance tax.

I don't know if financial planners created evasions like these post hoc or if they lobbied for these rules to help their clients avoid inheritance tax.

For Discussion

Here are some things to think about and comment on:

Do you agree with these desiderata? Are there other important ones? Are any of these either undesirable or not necessary?

Is this sort of top-down thinking about a tax system useful? It certainly doesn't seem that our legislators talk about taxes in these terms.

Next Up

Pros and Cons of Progressive Taxation

How do aspects of our current tax system stack up against these desiderata?

Politicians like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren call our tax system rigged in favor of the wealthy. How so? True?